A recovering 7 foot tall cactus

JSR first impressions

JSR is a new package repository being introduced by the team at Deno that aims to solve many problems in the Javascript eco-system. I was invited to take part in very early access to it and want to share my impressions.

A bit of history

I was a very early contributor to Deno which eventually ended up with me joining Deno when Ry and Bert got their seed funding. I left after two years to pursue work that was located in Australia.

During my time in the Deno community I created oak, an Express-like middleware framework written specifically for Deno. It still to this day remains a very popular framework. While I was at Deno, we often used it as a proving ground for things, like automatically generating documentation, making sure it worked on Deno Deploy, and other changes to the ecosystem.

I think its continued popularity and usage was one of reasons the Deno team reached out to me to give me very early access to JSR so I could see how it would work with something like oak.

What is JSR?

JSR is a Javascript/TypeScript registry. It is not a package manager. It is pretty clear that npm was the first viable package manager and registry for the Javascript ecosystem. Since then we have seen a lot of innovation in the package manager side of the equation, with yarn, pnpm, and even run-times integrating that package manager like Bun.

This was all innovation on the package management side. There has been little change or innovation on the registry side that still has the npm registry at its core. There have been corporate solutions which deal with things like private repositories and "allow-listing" approved packages, there have been solutions to enhance the npm registry, like unpkg and esm.sh, and while useful, they are still intrinsically coupled to the npm eco-system.

We in Deno tried to make a go of package-manager-less registry with deno.land/x which worked somewhat well for Deno which focused on "package management as code", but it has had it challenges. Ones that we were talking about before I left Deno.

JSR appears to be trying to innovate on that package registry side. Javascript has come a long way since the early days of npm. The npm registry and package manager were purpose built to serve a single runtime (Node.js) which was introducing the world to the concept of Javascript modules which came out of a community effort to scale JavaScript. We only really remember CommonJS for its module syntax adopted by Node.js, but it was originally a lot more.

Now the Javascript eco-system is a lot different. We have a language that has transformed itself, we have a standard for modules that services both server run-times and client browsers, we have a world where TypeScript is as dominate of a way to author Javascript code as Javascript by itself, and we have a breadth of local server run-times, serverless run-times, and browsers.

What is it trying to solve?

I didn't get a brief from the Deno team on JSR, or its roadmap, so a lot of this is formed from what I have seen using JSR.

The first thing it appears to try to solve are the challenges that we ran into with deno.land/x and the

package-manager as code approach to managing dependencies. When it works, it is a great development experience, just

focus on authoring code. The problem then comes in trying to express version dependencies. Each external dependency on

deno.land/x is "pinned" to an exact version. This is great from a "stability" method, but harder when common libraries

are shared across packages. JSR supports semver expression of dependencies. While this has been in the npm world

from the start, for Deno users, this allows the flexibility and benefit of package-manager as code, but with the

benefits of not always pinning to a specific version.

Another problem that JSR appears to be trying to solve is fully supporting TypeScript alongside Javascript. TypeScript didn't exist with the creation of npm and the solutions around TypeScript the community have arrived at really work around the challenges. It is confusing for package maintainers, "do I ship both transpiled and source TypeScript code? If I ship both, how do I help the users consume the package?" It is a real mess. In JSR you publish your source, be it TypeScript or Javascript, and the registry makes sure that the users consume the right version of code.

In addition, published code is "zapped" (which appears to be originally called FastCheck bit is migrating to Zap, which I suspect is because of the testing libraries that conflict with "fast check"). This appears to be a level of TypeScript type checking that can be accomplished without control flow analysis, looking at the public API surface of the package. The upside is that Zap is extremely fast, my antidotal evidence on oak is that it is about 10x - 15x faster. It also ensures that the published code can be fully documented via automatic document generation.

For package author's JSR aspires to write once, run everywhere. While it wasn't present in the early versions I played with and still has a ways to go, I recently took the ability to load JSR packages via Node.js and npm. The registry is runtime aware in that the package creator publishes a single version and the registry handles serving up a version specific to the target runtime. At the moment, the expectation is that the code is "aware" of the differences in the runtime, but I suspect, in the near future there will be ways to enable different ways of handling this. The Deno team created dnt a while back and hopefully we will see some of the features and ideas leveraged there work their way into JSR.

Enrich the package development experience is an apparent goal. Back when I was at Deno, we worked to improve the

development experience with deno.land/x so that package maintainers had a full suite of capabilities to improve their

downstream users development experience. The larger npm eco-system has innovated on that, and

npmjs.org has enriched the data to a degree based on these innovations, but it still isn't the

whole solution. One of the big things we did with deno.land/x which has been brought into JSR, is the automatic

generation of documentation. The same mechanisms package authors use to enrich the IDE experience through JSDoc and

TypeScript type annotations is used to generate rich online documentation for each package.

One of the advantages of Deno has always been the ability to use and TypeScript code as a first class citizen. It means that as a package creator, I don't have to figure out a way to distribute my type information alongside my runtime code (or make the consumer of the package do it). This non-Deno eco-system challenge has led some package authors to abandon developing in TypeScript in favour of authoring in "types-as-comments" JavaScript. That approach comes with its own complexities. I have it on good authority that while it isn't part of JSR at the moment, very soon JSR will generate type definitions along with transpile Javascript code when targeting the npm ecosystem. This means package authors can write in TypeScript and users will be able to consume the packages without need for either to worry about transpiling but have the ability to preserve the full IDE experience uplift and type checking that comes from using TypeScript.

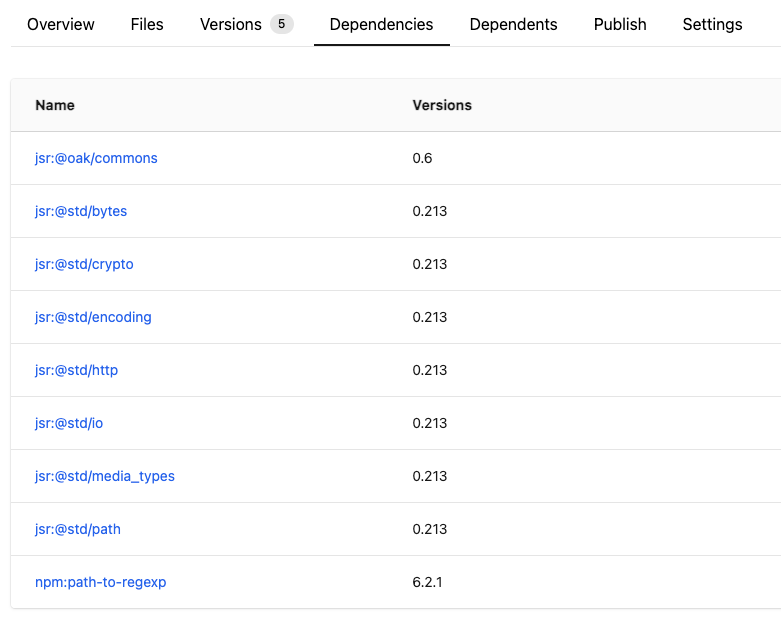

Capabilities and intelligent limitations

Code being published on JSR can only depend upon other JSR packages, npm packages, or Node.js built-ins. This walled garden appears to be an intentional limitation/constraint. This makes sure that the registry eco-system is contained and controllable.

But having access to the wider npm eco-system is transparent to both the package author as well as the downstream user,

and it uses the "package-manager as code" style of management. For example, I use the great

path-to-regexp library in oak. For the deno.land/x version I publish I

use the version that someone published to deno.land/x. In the walled garden of JSR, a version would have to be

published to JSR (which I am sure the package maintainer is unlikely to be interested in any time soon), or I could just

use the version on npm. This is what I chose when publishing on npm. I re-export all my dependencies from a ./deps.ts

file in oak and this is what it looks like there:

export {

compile,

type Key,

match as pathMatch,

parse as pathParse,

type ParseOptions,

pathToRegexp,

type TokensToRegexpOptions,

} from "npm:path-to-regexp@6.2.1";Another intentional limitation is that all published packages have to have fully qualified module names for internal code. This is to avoid the challenge that Node.js and the rest of the eco-system have had to try to unpick with how to interpret modules without explicit resolution.

One of the things that npm was sort of weak on was a lot of dependency on convention of what the public API service of a

package was. That has been slowly addressed through the addition of "exports" to package.json. With JSR, this is

explicit as well. As an author you have to either supply just a "main" exported module, or a map of various named

exports and their module. For oak, I export everything, but have added named exports for various public parts of oak. It

looks like this in the deno.json (which is the single meta-data file for JSR packages):

{

"name": "@oak/oak",

"version": "13.1.0",

"exports": {

".": "./mod.ts",

"./application": "./application.ts",

"./body": "./body.ts",

"./context": "./context.ts",

"./helpers": "./helpers.ts",

"./etag": "./etag.ts",

"./form_data": "./form_data.ts",

"./http_server_native": "./http_server_native.ts",

"./proxy": "./middleware/proxy.ts",

"./range": "./range.ts",

"./request": "./request.ts",

"./response": "./response.ts",

"./router": "./router.ts",

"./send": "./send.ts",

"./serve": "./middleware/serve.ts",

"./testing": "./testing.ts"

}

}As you can see from the above, there are now "name" and "version" fields that go into the deno.json which are then

used for publishing as well.

The Deno CLI is the publishing too for packages to JSR. It contains everything you need as a package author. To publish

a version, you simply do deno publish and away you go. The CLI will do all the checks and the like and even includes

the --dry-run option to make sure it behaves. The interface, while adequate, is obviously still maturing.

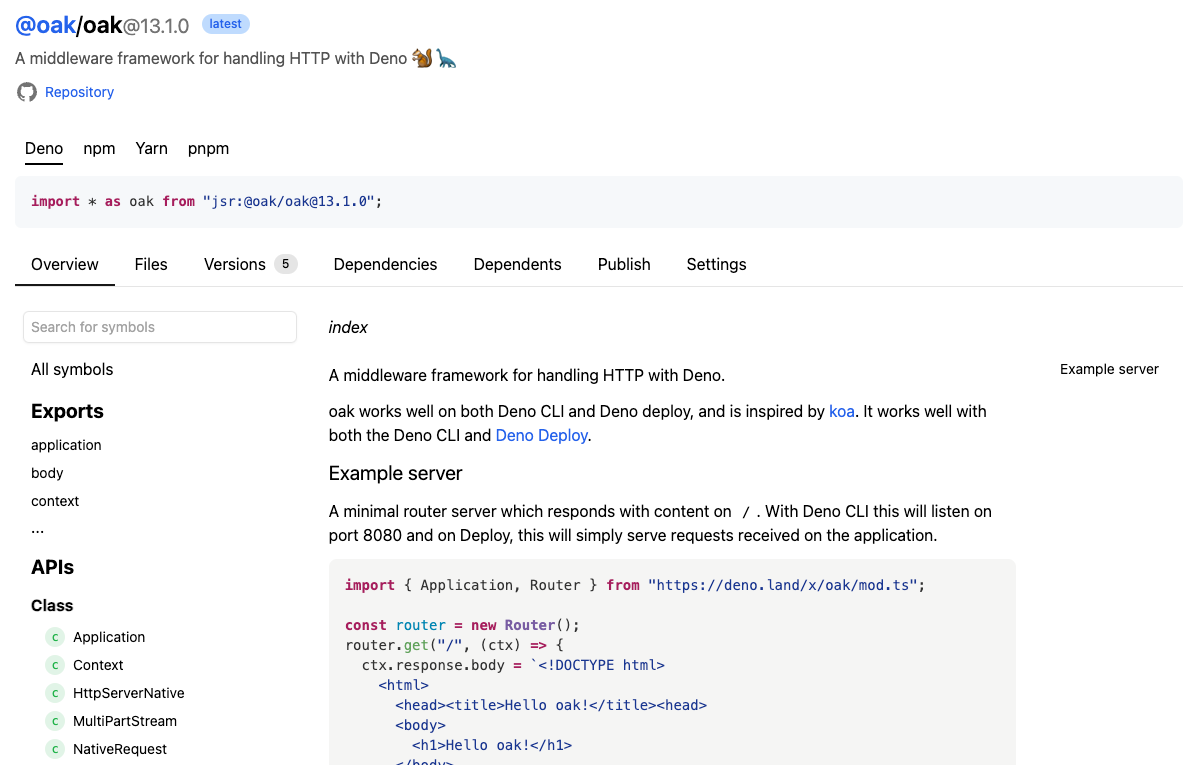

The registry interface

The registry web interface is already pretty rich. It is obviously building on a lot of what we did for deno.land/x

but it clearly takes it all to the next level. For those of you familiar with deno.land/x, a lot will be familiar, but

for those of you not familiar, you can see how the amount of information available goes beyond what we currently get

through the npm-ecosystem, all in one place.

This is what the oak package landing page looks like on JSR:

Because I have a module JSDoc block in the main entrypoint of oak, it is displaying that as the main document versus the README. If it wasn't present, it would have displayed the README instead.

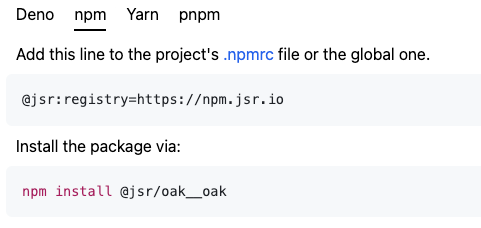

There are instructions on how to install a package under npm (or other npm-ecosystem package managers):

The instructions work, but the problem is that the code published to oak doesn't support Node.js yet. While I do publish oak to npm directly at the moment and that version works and is tested under Node.js, the same solutions for providing that capability aren't built into JSR. I have provided the team my feedback on this and hopefully we will see improvements in that area. I will also see if I can find a way to support both runtimes under the single JSR version.

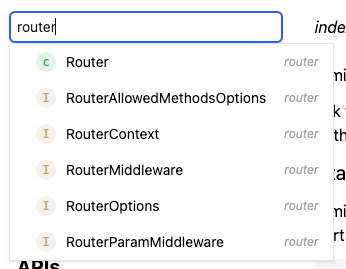

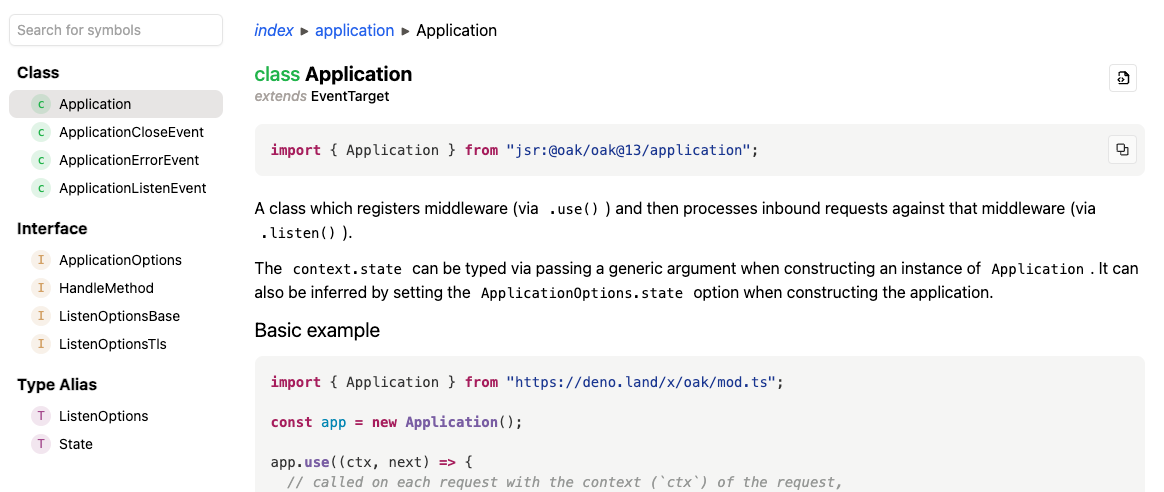

One of the great thing we experimented with on deno.land/x but had a hard time getting right appears to have been

integrated directly in JSR, the ability to search for symbols:

Here is the view of the dependencies for oak on JSR, where you express all your dependencies as code including the semver constraints which is automatically analyzed when you publish:

There is clearly an opportunity here to further enrich this with other data like if the dependency is current, or what are the changes the semver actually resolves to.

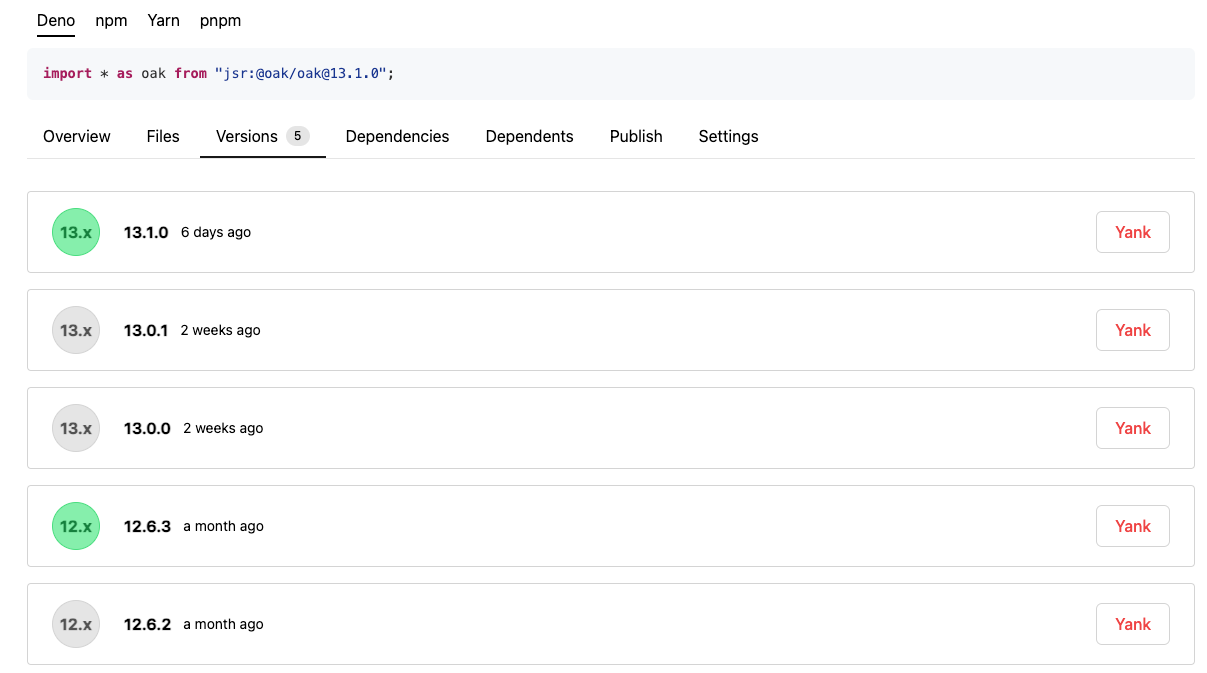

You also get a view of the versions published on the registry of a package, because I am the owner of the package, I also have the ability to "yank" a version:

The auto-generation of documentation was one of the most rewarding things I worked on for deno.land/x and I love that

it has continued through to JSR:

When embraced, this is a huge boost to developer productivity. It also makes the package maintainers life a lot easier, where you worry about writing your code and the same mechanism uplifting the developer experience in the IDE becomes the mechanism for documenting your package. Even without effort by the package author, you provide correct up-to-date documentation as a baseline.

Conclusions

JSR is still in the early stages. My initial impressions a month ago was that it was a fair amount of work for me to migrate oak to JSR. Some of that was the early stages and I was falling into problems that are now resolved and some of them are still being worked out.

Initially I was missing the "yeah, so what", but as more of the vision has started to reveal itself, the more excited I am getting.

It solves a lot of the problems that deno.land/x had, but in a way the preserves all the advantages that a

"package-management as code" brings. Add to that the ability to interoperate with the rest of the Javascript eco-system

is really solving a lot of real problems.

At the very least, having a registry that brings TypeScript on equal footing with Javascript is substantial. It is an advantage we have had in Deno land for years, but not something easily accessible to the rest of the Javascript eco-system until now.

So while it is still very very early, and obviously the eco-system will vote with its feet, I see some method to what on the surface was just a madness a little while ago.

oak example using JSR

Here is an example of using a version of oak off of JSR. This should be fully runnable with recent versions of the Deno CLI. (Deno Deploy doesn't currently support JSR, but I hear that is coming very soon.)

import { Application, Context, isHttpError, Router, RouterContext, Status } from "jsr:@oak/oak@13";

interface Book {

id: string;

title: string;

author: string;

}

const books = new Map<string, Book>();

books.set("1234", {

id: "1234",

title: "The Hound of the Baskervilles",

author: "Conan Doyle, Author",

});

function notFound(context: Context) {

context.response.status = Status.NotFound;

context.response.body = `<html><body><h1>404 - Not Found</h1><p>Path <code>${context.request.url}</code> not found.`;

}

const router = new Router();

router

.get("/", (context) => {

context.response.body = "Hello world!";

})

.get("/book", (context) => {

context.response.body = Array.from(books.values());

})

.get("/book/:id", (context) => {

if (context.params && books.has(context.params.id)) {

context.response.body = books.get(context.params.id);

} else {

return notFound(context);

}

});

const app = new Application();

// Logger

app.use(async (context, next) => {

await next();

const rt = context.response.headers.get("X-Response-Time");

console.log(

`%c${context.request.method} %c${decodeURIComponent(context.request.url.pathname)}%c - %c${rt}`,

"color:green",

"color:cyan",

"color:none",

"font-weight: bold",

);

});

// Response Time

app.use(async (context, next) => {

const start = Date.now();

await next();

const ms = Date.now() - start;

context.response.headers.set("X-Response-Time", `${ms}ms`);

});

// Error handler

app.use(async (context, next) => {

try {

await next();

} catch (err) {

if (isHttpError(err)) {

context.response.status = err.status;

const { message, status, stack } = err;

if (context.request.accepts("json")) {

context.response.body = { message, status, stack };

context.response.type = "json";

} else {

context.response.body = `${status} ${message}\n\n${stack ?? ""}`;

context.response.type = "text/plain";

}

} else {

console.log(err);

throw err;

}

}

});

// Use the router

app.use(router.routes());

app.use(router.allowedMethods());

// A basic 404 page

app.use(notFound);

app.addEventListener("listen", ({ hostname, port, serverType }) => {

console.log(

`%cStart listening on %c${hostname}:${port}`,

"font-weight:bold",

"color:yellow",

);

console.log(` using HTTP server: %c${serverType}`, "color:yellow");

});

await app.listen();